The time is coming for the final minutes of diploma work. Now, I take a moment to review some of the most important reviews I’ve had in the past months, trying to extract some useful ideas for what will be my final presentation.

La hora se acerca para el final de la tesis. Ahora me tomo un momento para repasar algunos de los comentarios más útiles que he recibido en los últimos meses, tratando de extraer ideas para mi presentación final.

—–

The following was commented on a personalized tutorial with Gisle Løkken on April 30th:

Allowed vs Not Allowed

– What is legally allowed, from the architectural point of view, in Rosengård?

– When people consciously know that they are acting in a legal context, there is no need for things such as police intervention.

– Allowing is a way to connect.

– Think an approach to public space that includes opening up, itinerancy and independence.

My experience

– Fantoft Pizza: study further in detail.

– The tale of the two afghans of Tromsø by Gisle: they offered a service no one else in town could offer.

– Study the typical markets in Guatemala.

– Land use in Greenland: public or private? The importance of a neighborhood council.

The importance of work

– To make money = to achieve independence

– Allow people to make an honest living!

Reaction

– The project not as an answer, but as a method.

– Work in ALL of Rosengård, but select sites to show.

– Enclaves of activity: exploiting the comparative advantages and existing conditions.

– Inclusion: people have got to be part of the solution.

Jean Paul Sartre: I am what I do.

—–

The following was commented on a tutorial headed by Gisle Løkken, and with the participation of other students on May 25th:

– To propose Rosengård as a kind of temporary tax-haven, with site-specific trade laws to allow commerce to flourish more easily.

– How would economic development affect the community? What would change in the face of the neighborhood in relation to this development? And how would these changes relate to the people who live there? Think of this project’s evolution in time: (un)projected growth.

– Gardening vs Farming: what is more realistic and productive for a place like Rosengård? Show this in the project, make plant-growing a VISIBLE activity.

– “I wanna see the goats” – Can Rosengård have space for activities like shepharding, and other seemingly out-of-place trades?

– The meaning of work as a tool, socially and ethically, in human development, applied to the people who live in Rosengård.

—–

On Thursday 27th and Friday 28th of May, the Third Confrontation for the diploma took place in the school. Working under Trudi Jaeger (DAV) and Sverre Sondresen (APP), the following are points that were mentioned in relation to my project:

– The project as a reason for people to stay in Rosengård. So far, people have very few reasons to stay in the community. Could this project be a start for change?

– Joint solutions coming from both the authorities and the people.

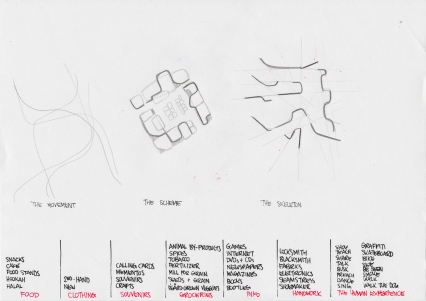

– A bazaar proposal that makes use of the public AND the private space. Not only as a “new” activity built in space, but also making use of existing spaces: firs t floors, corner shops, etc.

– The project as a multicultural quilt, where every patch is equally valuable and yet as unique and “on display” as the rest.

– The bazaar: a nice place to be, a nice place to visit. Visiting Rosengård has the great potential of acting as a reality check: people coming here to a bazaar will find a community eager to work and earn a better life, opposed to the riots that Rosengård is known for.

– Simplify my registration drawings, keeping the energy and feelings found in them while incorporating colour to represent the variety found in Rosengård.

– The pic-nic blanket: a place to display, make evident and share.

– Build more models of the actual projects, in different scales. Explore materiality (remember the differences between shopping mall and bazaar when it comes to the sensorial experience), use and scale for design purposes. Very important now.

– If you are too realist, you end up becoming a pessimist. Therefore, it is important to remember the poetry of dreaming.

– Graffiti as a way to deal with frustration and establish an identity. Rosengård is notoriously devoid of graffiti, is this the sign of a population that does not want to be associated with their neighborhood? Additionally, could architecture offer a chance to reterritorialize the neighborhood and make it “valid” to display your pride to live in Rosengård?

– “Graffiti is like when dogs pee. They are not vandalizing a wall. They are defining their territory.”

– Define a strategy / timeline: how does the project grow and evolve? Who does it affect? What will the actions cause? Can it be a kind of chain reaction, where small actions end up causing full blown effects? This is already suggested in the yellow Post Its (see previous entries).

– Use drawings as a design and exploration tool: draw in big sizes (scale up); incorporate to exhibition space; work on the same drawings throughout a span of time – evolution; print on transparent paper for further exploration; use drawings to re-structure the spatial reality of the neighborhood and the project.

– Check several influences: Le Corbusier’s drawings for Le Petit Cabineau, Cy Twombly (pay special attention at how he activates space), others.

-Mental note: don’t assume people know about the context of the project. Explain very clearly what is The Million Programme and other relevant concepts in the context of this project.

– The project as a “happy bomb”? After all, these boxes (namely, the apartment blocks) hold a lot of frustration.

– Find out as soon as possible where will my exhibition space be, and start thinking my presentation accordingly.

– The use of scale in Rosengård’s existing condition: brutal. Bring it back to human.

– Think about 1:1 sketch. A possibility is to explore how people appropriate a public space.

_____

El jueves 27 y viernes 28 de mayo tuvo lugar la tercera confrontación en el proceso del diploma. Bajo la guía de Trudi Jaeger y Sverre Sondresen, estos son los puntos mencionados en relación a mi proyecto:

– El proyecto como razón para quedarse en Rosengård. Hasta la fecha, la gente tiene pocas razones para quedarse en el barrio. ¿Podría este proyecto cambiar tal realidad?

– Soluciones conjuntas involucrando tanto la comunidad como las autoridades.

– Una propuesta de bazaar que use tanto el espacio público como el privado, de tal manera que no sólo se genere actividades nuevas, sino que también se use espacios existentes: primeros pisos, pulperías, etc.

– El proyecto como un tejido multicultural, donde cada parte es igualmente valiosa, única y puesta en exhibición como las demás.

– El bazaar: un buen lugar donde estar, un buen lugar para visitar. Una visita a Rosengård tiene el potencial de actuar como un vistazo a la realidad: la gente viniendo a la comunidad encontrará residentes trabajando y ganándose la vida honradamente, muy distinto a los disturbios por los que Rosengård es conocido.

– Simplificar mis bocetos, manteniendo la energía y emociones en ellos a la vez que se incorpora color para mostrar la variedad encontrada en Rosengård.

– La sábana del día de campo: un lugar para mostrar, hacer evidente y compartir.

– Hacer más modelos del proyecto como tal, en distintas escalas. Explorar materiales (y recordar las diferencias entre un centro comercial y un bazaar en cuanto a la experiencia sensorial), el uso y la escala para propósitos de diseño. Punto muy importante.

– Si se es muy realista, uno termina siendo un pesimista. Por ende, es importante recordar la poesía de soñar.

– El grafiti como una manera de lidiar con la frustración y establecer una identidad. Notablemente, las paredes de Rosengård carecen de grafiti. ¿Es esto la señal de una población que no quiere ser asociada con su barrio? La arquitectura puede ofrecer una oportunidad para reterritorializar el barrio y convertirlo en un lugar donde es válido mostrar orgullo de vivir en Rosengård.

– “El grafiti es como cuando un perro orina. No es un acto de vandalismo, sino uno de territorialidad.”

– Definir una estrategia o línea de tiempo: ¿cómo crece y evoluciona el proyecto? ¿a quiénes involucra? ¿qué consecuencias habrá? ¿puede ser como una reacción en cadena, donde pequeñas acciones terminan causando grandes efectos? Esto ya se sugiere en los Post Its amarillos mostrados anteriormente en este blog.

– Usar el dibujo como una herramienta de exploración y diseño: dibujar en gran formato; incorporar el dibujo al espacio de exhibición; trabajar en un mismo dibujo a través de un cierto lapso de tiempo – evolución; imprimir en papel transparente para posterior exploración; usar dibujos para re-estructurar la realidad espacial del barrio y el proyecto.

– Influencias: los dibujos de Le Corbusier para Le Petit Cabineau, el arte de Cy Twombly y su activación del espacio, otras.

– Nota mental: no asumir que la gente conoce el contexto del proyecto. Explicar claramente qué es el Proyecto del Millón y otros conceptos relevantes para el contexto de este proyecto.

– El proyecto como una “bomba feliz”. Después de todo, estos cajones (los edificios de apartamentos) contienen mucha frustración.

– Hallar cuanto antes dónde voy a exponer y conceptualizar mi presentación final de manera acorde.

– El uso de la escala en la realidad actual de Rosengård: brutal. Devolver al ser humano.

– Pensar en el boceto 1:1. Una posibilidad es explorer cómo la gente se apropia de espacios públicos.

—–

The following was written by Trudi Jeager:

Report after 3rd confrontation 28.mai 2010.

Sverre and Trudi.

City in a specially challenging condition (liminal situation).

We asked all the students in the group to present their projects concisely with a short synopsis. Sverre and I didn’t know anything. They were given 20 minutes each before lunch. The group were already collaborating with each other and were much more familiar with each others projects than either Sverre or I so we consigned everyone with a specific student. They were asked to give their person specific advice about what to concentrate on according to where they were in the process: i.e. to reflect upon a core issue. We others could then either disagree or elaborate on these observations.

Roberto:

Flying kites in the ghetto.

Malmø is one of the fastest-growing migrant areas in Scandinavia.

Bazaar – place where people can utilize and share their skills.

Roberto has vibrant drawing skills! This talent should be used! Make Graffiti idea much larger. Test it out in public space with participants.

A strategy on timeline – what it generates – a new structure.

Add something – open up.

Should focus his project on public space(s).

Discussion about graffiti, about conquering and taking space. The energy this sort of people-participation project would create, if, for example, people from different cultures were encouraged to ‘take’ their space.

Roberto should get locals to make their own marks in the area.

He should start concentrating by building a working model in i.e. 1-25 in order to develop the inter-relationships of the different cultural spaces and their interfaces.

——

On June 9th, I had a tutorial with Vibeke Jensen. We discussed the following (I add my own thoughts in this text):

0. General comments

– Explore the conceptual models more and more.

– Integrate gardening into activities like the skate park, and other functions as well. Why should this activity be confined to the colonial gardens?

– Work quickly with conceptual models, and move on to design.

– What I show does not necessarily need to be a finished product in itself, but it should enough detail and information to be understandable.

– Consider other activities and forms of expression, such as hand ad-painting, gossiping, etc.

1. The bazaar – Herrgården

– Make a model that shows inside space, not just the outside. Think of negative, carved space.

– The management of scale is good for the neighborhood’s inhuman conditions.

– An “exploded block” is a good concept. It shows the potential of a single block, the basic construction unit of Rosengård. Explore further consequences of this idea.

2. The promenade – Kryddgården

– The use of lines as a landscape-intervention concept is OK, but they should be soft, adding some contrast to the existing geometry.

– I should define the situations to happen between the buildings: the urban stages, sheltered spaces, community meeting points, etc.

– Integrate this intervention to the landscape, make it a part of the context and not just something that “landed there”.

– How much of a line do I need to show, in order to make a line? What does a line have to offer?

– Think of softer materials.

3. The skate park – Örtagården

– Keep in mind that it can be an activity that includes many people, not just young skateboarders. It can be a meeting point for people interested in urban culture, photography, curious neighbors… even grandmas. I don’t skate myself, I’m almost 30 and yet I am more interested than I ever was, in these activities.

– It can be a kind of agora, a meeting point where things happen. A change in Rosengård’s monofunctionality.

4. 1:1 Sketch

– Make architecture, create space!

– Construct situations, think of the situationist movement?

– Documentate, and get people included.

—–

Extracts from a June 9th conversation with Camilla Ryhl, KTF:

– Accesible architecture should not only be functional, but also available and open.

– When a person lacks one sense, the other senses sharpen. Think of how these other senses can be stimulated through architecture.

– Ground surfaces and materials can give a good amount of information.

– Be careful when it comes to overstimulation.

The bazaar

– Check out Gjellerup Parken in Aarhus.

– Shopping centres can be a difficult environment for the visually impaird. They offer no visual nagivational clues. They are the same in every direction. They are usually disconnected from their context.

– Take the characteristics of a shopping centre and create a contrast.

– Different-sized units and activity-enclaves in Rosengård are good ideas. They provide a sensorial spatial configuration.

– When it comes to the bazaar, take a couple of units and develop: how do they relate? What happens in between the units?

The skate park

– How do disabled people interact with it?

– A generational meeting place.

– Give more reasons for people to come here.

—–

Tutorial with Erling Olsen, TTA. June 15th, 2010. I intend to use different materials according to the needs of my sites. These are general comments from this conversation:

– Wood is slippery, but can be transformed and manipulated by people, as opposed to concrete, which offers little chance for interaction.

– Create friction in the surfaces. Winters and water can be dangerous.

– If I use wood, think that it won’t last forever, it will probably have to be replaced every 5 to 10 years. Additionally, wood expands and contracts and is vulnerable to fungus, so it must be isolated from moisture (rubber is a good option for this), both on roof and ground. If this wood is dry, it will last a long time.

– Think of detailing. Show how this will be built.

—–

Tutorial with Ivo Barros, Sivilarkitekt BAS. June 16th, 2010.

– How do I come to this place? Go from Zoom Out to Zoom In.

– Put my maps in order and try to read a coherent story there. From Scandinavia to Rosengård.

– Show Rosengård in relation to the city of Malmö and its context.

– Work as a masterplan, but show some areas more in detail -à Explain why I chose the sites I work with. Start working in a larger scale and then show how things meet.

– The relation of the intervention with the rest of the city: why would people from Malmö come to Rosengård? -à Think of the comparative advantages of my project and show them.

– Expand my interventions all the way to the main roads that limit Rosengård, and create invitations.

– Use my experience as a foreigner to my own advantage. I have some first-hand knowledge and different takes on issues like urban life, fear, etc.

DAV: the under-used tool

– Use DAV as an exploratory tool. Work with photos and drawings. Explore the 5 small conceptual models and work with them as ways to understand space.

60.345741

5.354213